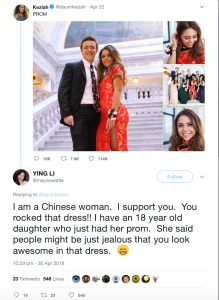

A recent Twitter storm brought back to the headlines the issue of how we relate to the culture of others. At the centre of this virtual melee was Ms Kezia Daum, a high school student from Salt Lake City, UT, who decided to wear a Chinese red cheongsam dress (also known as a qipao) she found in a vintage shop, to her high school prom in April of this year.

What happened next is perhaps all too predictable today: a barrage of criticisms, attacks and condemnations, all accusing her of ‘cultural appropriation’. Daum, who is not Chinese, the argument goes, is banned from wearing this dress, as doing so allegedly insults the cultural sensitivities of Chinese people. Accusations of ‘consumerism’ blend with those of ‘colonial attitude’ to create a rather toxic discourse about fashion, culture and vaguely formulated ideas about authenticity.

The story is actually reminiscent of a similar dispute about an exhibition in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts where visitors in 2015 were invited to put on a Japanese kimono and to pose in front of Claude Monet’s painting La Japonaise.

‘Kimono Wednesday’ was part of the travelling exhibition ‘Looking East: Western Artists and the Allure of Japan’ that came to Boston after stops in Tokyo, Kyoto and Nagoya, where the kimono was available for the same purpose. As the Boston MFA explained in an internal memo that was leaked to the press,

The chance to try on a kimono … just like Camille Monet’s in La Japonaise – present an opportunity to inform our visitors about ‘japonisme’ and the influence of Japanese art and culture on Monet and other Impressionists. It provides an opportunity for visitors how heavy the robe is; how it feels to war it; what choices the artist made in creating the pose; and how he used paint to capture the effects of the textile.

Yet this explanation did little to console the critics who claimed that allowing visitors to experience wearing the kimono was tantamount to winkingly acknowledging racial prejudices and Orientalism. In July 2015, the museum discontinued ‘Kimono Wednesday’.

There are some interesting similarities between these two cases in that, firstly, they both refer to the uses (and alleged abuses) of Asian garments. Secondly, in both cases arguments centre on ‘imperialism’, ‘colonialism’ and ‘racism’. Wearing the Asian dresses become a signifier of the worst of Western culture.

I very much disagree with these arguments.

Firstly, all fashion, indeed all culture, is appropriation. Elements of sartorial style freely cross cultural boundaries and become incorporated and absorbed within a fashion system that seeks sources of traditions and innovations wherever it can find it. This holds from the tacky, such as Americans in some sort of Dirndl and sneakers,

to the sublime, for instance the inspiration found in Chinese culture by Western designers as shown in the 2015 Met exhibition China Through the Looking Glass. The idea that sartorial practices should respect cultural boundaries misunderstands both the way fashion, and for that matter culture, operate. To cite another culture by wearing one of its garments simply repeats a move that characterises the relationship between cultures in a more general sense. No culture is pure, every one is permeated by other cultures’ infusions. This does not mean that power and politics can be ignored in these relationships. The fact that in both cases wearing Japanese or Chinese garments is deemed to be problematic suggest a post-colonial sensitivity that highlights lingering structures of domination and subordination between ‘the West’ and ‘the Orient’. But reading the vestimentary citation of other sartorial cultures as a unilateral exercise of power seems to be more of a forced and dogmatic interpretation than evidence of critical thinking.

The absence of any pure culture is also suggested in the observation that the qipao ‘was introduced by the Manchus, an ethnic minority group from China’s northeast — implying that the garment was itself appropriated by the majority Han Chinese’. Moreover, it ‘originally’ looked nothing like what we now know as a qipao; it was only in the 1920s and 30s, in the presence of Western cultural influence, ‘that the qipao was reinvented to become the seductive, body-hugging dress that many think of today’. If this is true (and I seem to recall that the catalogue of the China Through the Looking Glass exhibition, on my shelf back home in Washington, DC, confirms this), then the qiapao already has absorbed Western cultural influences as an aesthetic response to the Western gaze in early 20th century China.

A second counter-point starts with the observation that many commentators in both China and Japan don’t seem to live up to the expectations of Western post-colonial dogmatist. More often than not, the responses to ‘Kimono Wednesday’ and to the Chinese prom dress were rather positive, commending Ms Daum on her sartorial choice and praising the dress for it beauty, or expressing support for the idea of giving museum visitors the chance to try on a Japanese garment.

Japanese-Americans, Japanese residents in the United States and their supporters counter-protested at the museum and on social media in vain. Counter-protesters pointed out that very few of the protesters were Japanese, and that they had no right to dictate what counted as racism or cultural appropriation against Japanese or Japanese-Americans. They complained that the protesters had chosen the wrong event to protest against with their parochial identity politics agenda.

Said’s thesis of Orientalism, the article continues, seems hardly relevant to the relationship between Japan and the West. Japanese textile manufacturers happily accommodated the European fascination with Japonisme.And crucially,

For their part the Japanese reciprocated with their own fascination for, and assimilation of Western fashions. By then Japan was also a colonial power which was turning its own Occidentalist gaze — and naval guns — back on the Western powers. In such circumstances, Western fascination with Japan’s exotic arts and fashions fits a loose definition of Orientalism, but it is more benign than Said’s thesis allows for.

In the case of the Western – Chinese relations, the political background is clearly more problematic. Yet similarly, Ms Daum’s choice was vocally supported by Chinese-Americans

When the furor reached Asia, though, many seemed to be scratching their heads. Far from being critical of Ms. Daum, who is not Chinese, many people in mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan proclaimed her choice of the traditional high-necked dress as a victory for Chinese culture.

So what do we make of sartorial Orientalism when the targets of that nefarious practice refuse to accept the victimisation ascribed to them? L.H.M. Ling’s development of a ‘positive orientalism’ in her brilliant chapter in The International Politics of Fashion, based on a critical but sympathetic review of the 2015 Met Exhibition, might provide a start. Positive Orientalism reverses the hierarchy implied in negative Orientalism and appreciates the impact and influence Eastern imaginaries has on Western arts and aesthetics and the crucial debt Western culture owes to ‘the East’. Eastern culture and aesthetics, it bears emphasising, are more than accessories or additions to Western culture; they are, in a Derridian sense, supplements without which Western culture would not be what it historically has become. They are positive and affirmative traces of the Other in the West which have become an integral, yet identifiable, part of its culture. Moreover, fashion allows us to appreciate the even more intertwined relationship between culture via Guo Pei’s gold lamé gown at the Met exhibition that combines the Western evening gown with the Chinese or Buddhist lotus blossom design. What is Chinese and what is Western here is no longer clearly distinguishable, as culture mere into one another and create a truly sublime expression of what fashion is all about.

lydiaxliu via Wikimedia Commons

Arguably then, the claim of Orientalism as a condemnation (what Ling calls ‘negative Orientalism’) does not seem to capture the complex relationship between (sartorial) cultures. This is not to say that ‘anything goes’. Ling identifies some themes (the Saint Laurent room and his perfume ‘Opium’) and issues (the sexualisation of Chinese sartorial code in Western designs) that weave what she considers ‘negative Orientalism’ into whatever positive we can experience in this vestimentary encounter of cultures. This certainly invites a critical discussion about the limits of cultural exchange and the power involved in them. But the gist of the argument here militates against the facile rejection of any such exchange and the unilateral proclamation of outrage by the West on behalf of the East.

For this seems to be the central aspect of the acrimonious debates about a Chinese prom dress or a Japanese kimono. ‘We’, i.e., the West, speak and complain on behalf of the Oriental Other, we arrogate to ourselves once again the voice of the Other. Never mind that hardly any Chinese or Japanese person actually takes offense, we still proclaim our own moral failing in order to assert and assure ourselves of our own moral superiority. We know that we did wrong, and we shall remedy it by imposing upon ourselves punishment and retribution. I call this ‘custodial Orientalism’ in order to emphasise the perverse and contradictory hierarchy at play here. The accusatory claim of Orientalism elevates the (Asian) Other above the West and demands that we must not touch or contaminate it via ‘cultural appropriation’, yet at the same time this accusation empowers us to speak for the Other, to voice its condemnation against ourselves, and thereby claim our distinctive moral superiority above the Other and our Selves. Even when pronouncing on its own moral failure, the West still turns this into a manifestation of its own moral superiority.

Cool. Looking forward to reading this! 😎

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike

This is brilliant and gets at many of the reasons that claims of cultural appropriation bother me so much. AnythIng that smacks of a desire for purity, especially in matters of culture and identity, makes my hair stand on end.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Who came up with this cultural appropriation concept? Isn’t world civilization enriched by cultural sharing? Of course, it definitely depends on the intent of the person wearing the outfit. This young woman meant no disrespect at all and in fact looks quite lovely in it. Can’t we all just enjoy sharing our cultures? My biggest fear regarding the hysteria “cultural appropriation” is that it will lead to isolationism. If we isolate ourselves from each other a whole host of problems can arise. As societies we shouldn’t separate ourselves into groups and throw a fit if someone outside our group simply enjoys something we like to wear, cook, or eat. The world is a beautifully diverse place; let’s enjoy it, and share.

LikeLike